AlphaProof's Greatest Hits

Here I’ll try to explain the coolest ideas in each of AlphaProof’s IMO 2024 solutions. AlphaProof produces proofs in Lean, and each Lean proof is composed of a series of tactics. So I’ll pick out the tactics that correspond to these ideas in the proofs for problems 1, 2 and 6 (the three problems that AlphaProof solved). AlphaProof has developed its own proving style, so figuring out what it’s doing can involve some detective work.

If you’re not familiar with the problems already, I recommend trying them yourself, and then maybe reading Evan Chen’s solution notes, or watching these videos that give an intuition for some of the human solutions. The full AlphaProof solutions, annotated by Lean experts, are available here - I will only include snippets of the proofs in this post.

Problem 1

Problem

Determine all real numbers $\alpha$ such that, for every positive integer $n$, the integer

\[\lfloor \alpha \rfloor + \lfloor 2\alpha \rfloor + \dots +\lfloor n\alpha \rfloor\]is a multiple of $n$. (Note that $\lfloor z \rfloor$ denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to $z$. For example, $\lfloor -\pi \rfloor = -4$ and $\lfloor 2 \rfloor = \lfloor 2.9 \rfloor = 2$.)

Solution

The answer turns out to be the set of even integers. Reminder that the way AlphaProof solves these problems is by proposing many solution candidates, attempting to prove and disprove each of them, and then eventually finding a proof only for the correct answer. The proof we’re looking at here is the one that proves that the answer is the set of even integers.

Showing that the even integers satisfy the given property is trivial, the hard part of this proof is to show that no $\alpha$ except the even integers can satisfy it. AlphaProof does this in an interesting (if convoluted) way. It first sets up an integer $\ell$ such that $2\ell = \lfloor\alpha\rfloor + \lfloor2\alpha\rfloor$. This is possible because we know the RHS is even by substituting $n=2$ into the given property.

existsλx L=>(L 2 two_pos).rec λl Y=>?_L 2 is where the given property is used with $n=2$. As an aside, AlphaProof often mashes several tactics together in a single line like this. A more comprehensible version that accomplishes the same thing is

constructor

· intro x L

obtain ⟨l, Y⟩ := L 2 (by exact two_pos)Note that we’ve also renamed $\alpha$ to x.

Next, it claims (and goes on to prove) that for all natural numbers $n$,

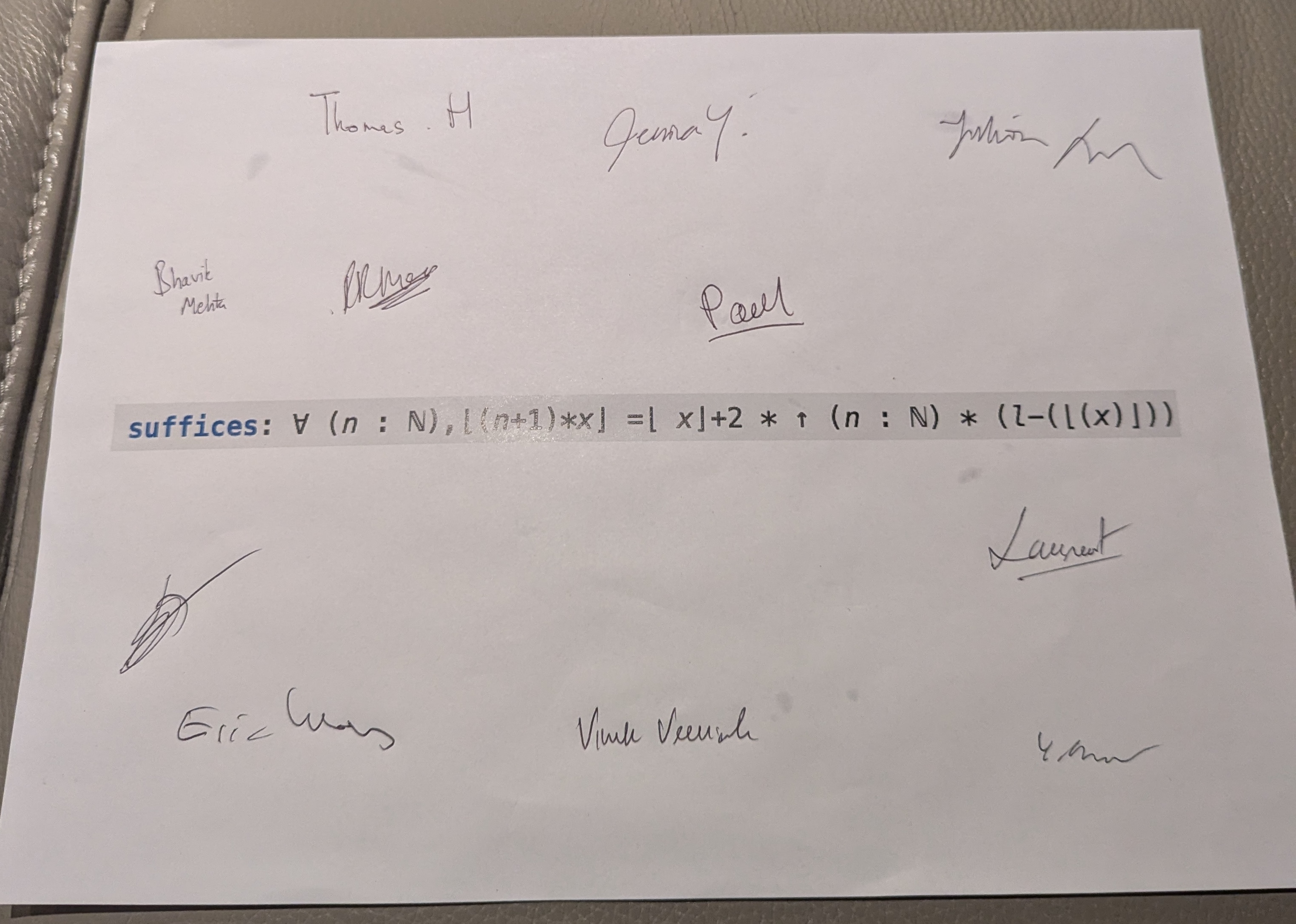

suffices: ∀ (n : ℕ),⌊(n+1)*x⌋ =⌊ x⌋+2 * ↑ (n : ℕ) * (l-(⌊(x)⌋))From this, it is able to show that $\alpha = 2\,(\ell-\lfloor\alpha\rfloor)$.

use(l-⌊x⌋)*2which has to be an even integer (since it’s 2 multiplied by an integer).

The way in which it proves these things involves some rather elaborate simplifications. But setting up the claim in \eqref{eq:claim} is the impressive bit that makes the rest of the proof work. To my eyes, the motivation for this claim is rather unintuitive, and the fact that it all works out is almost magical.

AlphaProof’s full solution is here.

Problem 2

Problem

Find all positive integer pairs $(a,b)$ such that there exist positive integers $g$ and $N$ where

\[\gcd\,(a^n + b, b^n + a) = g\]holds for all integers $n \geq N$.

Solution

AlphaProof correctly proposes that $(1, 1)$ is the only solution. To show that no other solution can work, it asks us to consider the number $ab + 1$. It claims (and later proves) that $ab + 1$ must divide $g$.

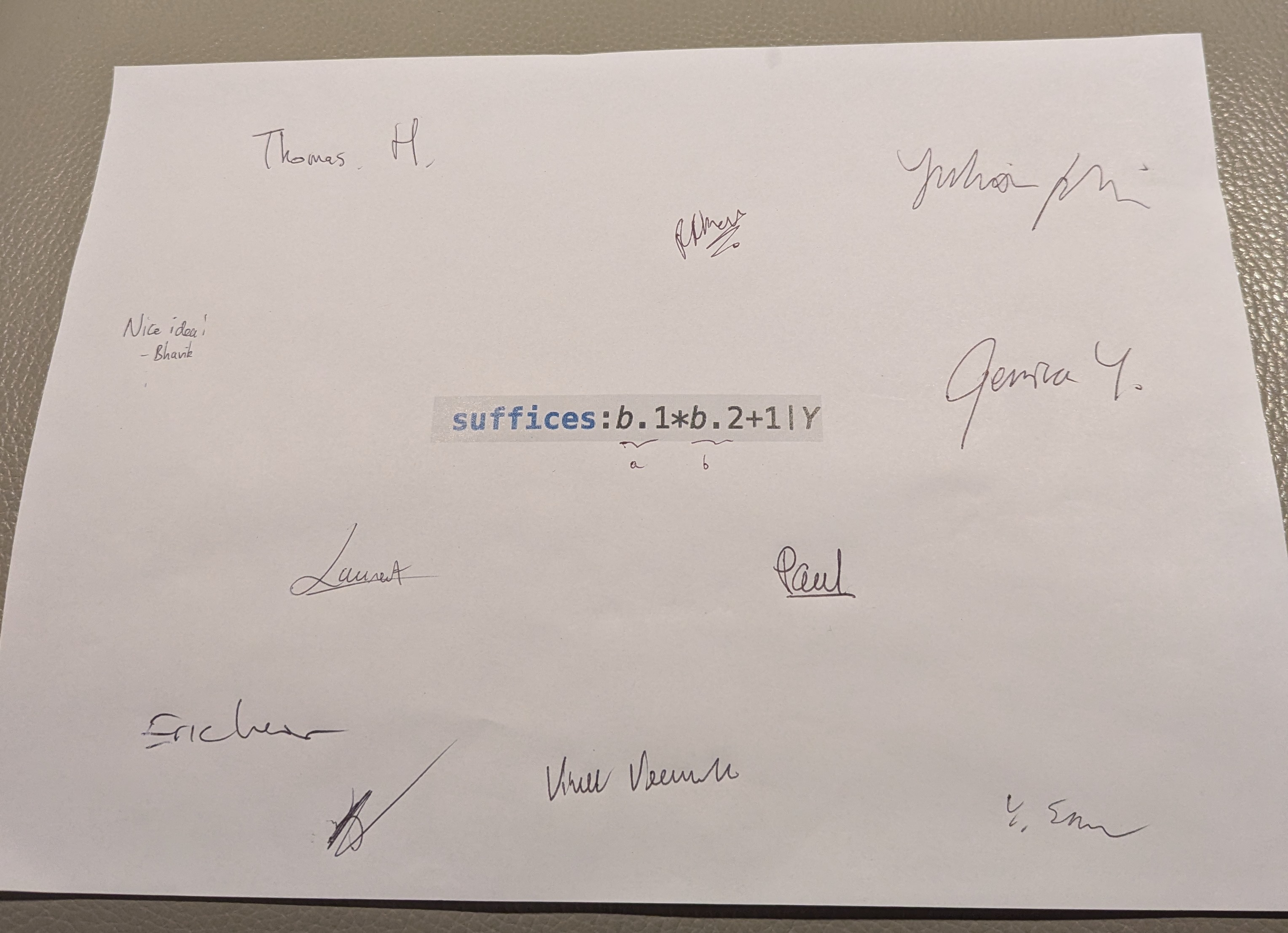

suffices:b.1*b.2+1∣YNote that in its infinite wisdom, AlphaProof decides to rename pairs $(a, b)$ to b, so that it must reference the elements as b.1 and b.2. It has also chosen, for reasons best known to itself, to rename the variable $g$ to Y.

Now, selecting $n=N \phi(ab+1)$, we get

\[(ab + 1) \mid (a^{N\phi(ab + 1)} + b) \text{ and } (ab + 1) \mid (b^{N\phi(ab + 1)} + a)\]The fact that $ab + 1$ is coprime to $a$ and $b$ makes it so that we can apply Euler’s theorem, ie

\[a^{\phi(ab+1)} \equiv 1 \pmod{ab+1}\] \[b^{\phi(ab+1)} \equiv 1 \pmod{ab+1}\]So we have $ab + 1 \mid 1 + b$ and $ab + 1 \mid 1 + a$, from which it follows that $a = b = 1$.

This strategy closely follows human proofs to this problem. The choice to consider $ab + 1$ is the clever idea that sets up the proof.

AlphaProof’s full solution is here.

Problem 6

Problem

Let $\mathbb{Q}$ be the set of rational numbers. A function $f: \mathbb{Q} \to \mathbb{Q}$ is called aquaesulian if the following property holds: for every $x,y \in \mathbb{Q}$,

\[f(x+f(y)) = f(x) + y \quad \text{or} \quad f(f(x)+y) = x + f(y).\]Show that there exists an integer $c$ such that for any aquaesulian function $f$ there are at most $c$ different rational numbers of the form $f(r) + f(-r)$ for some rational number $r$, and find the smallest possible value of $c$.

Solution

AlphaProof finds the answer $c=2$. It breaks the proof into two parts. First, it shows that $c \leq 2$, by showing that $f(r) + f(-r)$ can either be $0$ or some singular other value. This part of the proof is quite elaborate, and makes clever use of the given aquaesulian properties.

Once this is done, $c$ can be either $1$ or $2$. To show that $c=2$, AlphaProof proposes an aquaesulian function $f$ that takes on two different values for $f(r) + f(-r)$.

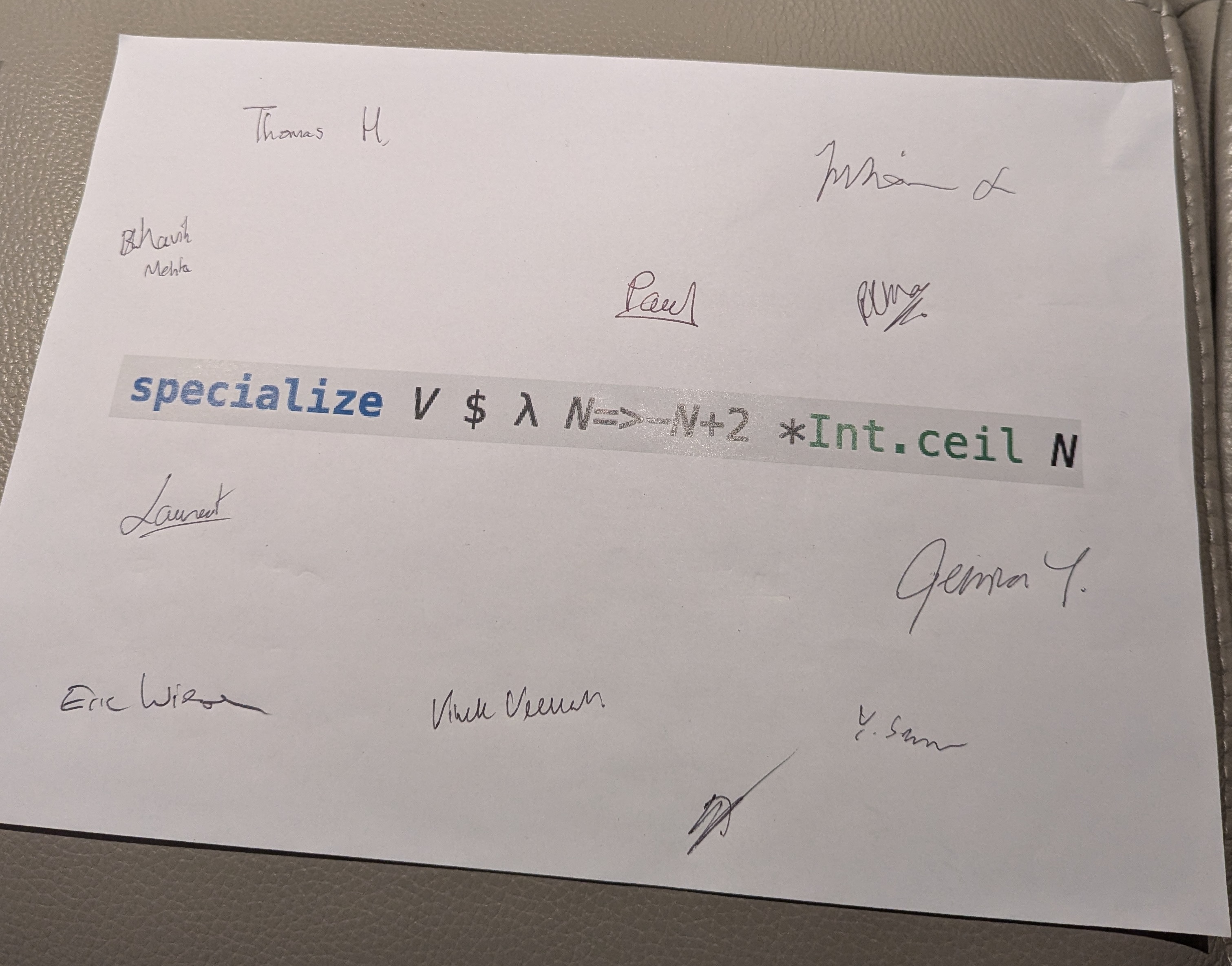

\[f(x) = -x + 2⌈x⌉\]specialize V $ λ N=>-N+2 *Int.ceil NIt then shows that $f(-1) + f(1) = 0$ and $f(1/2) + f(-1/2) = 2$, which gives us the two distinct values we need.

use Finset.one_lt_card.2$ by exists@0,V.1.mem_toFinset.2 (by exists-1),2,V.1.mem_toFinset.2 (by exists 1/2)Again, lots of stuff mashed into one line, but by exists -1 and by exists 1/2 are where it shows the two distinct values.

This is a remarkable function to have constructed! And it’s pretty hard to find. Only 5/509 participants solved P6, and notably Tim Gowers gave it a bit of a shot while judging this solution and didn’t find a function that gave two distinct values.

AlphaProof’s full solution is here.

Postscript

Having now digested several AlphaProof solutions, I still find it remarkable that a machine is able to find proofs like this. Finding these mathematical ideas is hard enough, and having to prove them in Lean makes things even harder.

At an IMO afterparty, some of us from the AlphaProof team had fun with signing the best tactic from each proof.

I discussed the P6 solution in some more detail on the No Priors podcast.

Thanks to the Lean experts who translated the cryptic Lean proofs into English, and Bhavik, Oliver and Paul in particular for suggesting impressive lines in the proofs.